Is EBITDA a proxy for Cash Flow?

Leo Hindery: “We’re the kings and the queens of EBITDA, we’re all about cash flow, pre-tax cash flow, and we try not to pay taxes. And I don’t view that as anything but positive.”

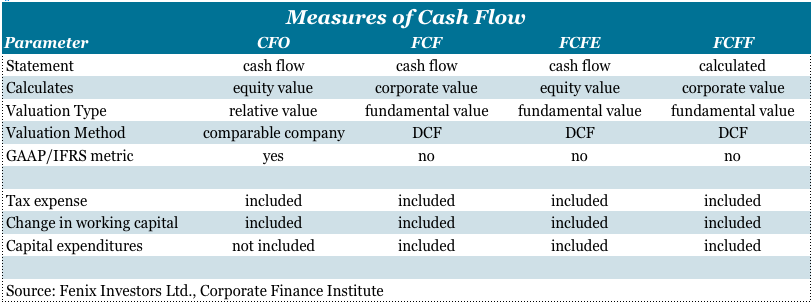

Cash flow is measured by the cash flow statement. Cash flow has a multitude of definitions, including cash flow from operations, free cash flow, free cash flow to equity and free cash flow to the firm.

While cash flow is a generic term, investors prefer free cash flow, a non-GAAP metric that represents the cash flow that is available to the company’s securities holders. Free cash flow also captures the notion that capital expenditures are necessary to create, to sustain and to expand a company’s competitive advantage.

EBITDA measures accounting profits, not cash flow. EBITDA is generally not a suitable proxy for cash flow, since EBITDA is an income statement metric. As a measure of accounting profits, EBITDA is an accounting metric based on accrual accounting, and EBITDA excludes interest expenses and tax expenses. Further, EBITDA excludes investments in short-term assets (i.e. working capital) and long-term assets (i.e. capital expenditures).

As VAR is an analytically flawed proxy for risk, EBITDA is an analytically flawed proxy for cash flow. EBITDA is superficially mistaken as a proxy for cash flow, since it is “above the line”. Therefore, people mistakenly conclude that EBITDA is a measure of a company’s operating performance. Since cash flow is a non-GAAP metric, operating managers have the creative liberty to define cash flow, and operating managers have an incentive to overstate a company’s cash flow performance. Since EBITDA invariably produces a higher number, operating managers often advance EBITDA as a proxy for cash flow.

The Shift from Post-tax Earnings (EPS) to Pre-tax Earnings (EBIT)

Historically, corporate performance was measured by earnings per share (EPS). Over time, operating managers began to advocate for performance metrics based on pre-tax earnings rather than post-tax earnings, and operating managers advocated EBIT as the measure of corporate performance.

EBIT became the preferred proxy for cash flow despite its imperfections. Driven by the preference for simplicity, people began to use an income statement metric as a proxy for cash flow. However, EBIT and cash flow are calculated using completely different accounting methods. Accrual accounting counts a sale when a product ships to the retailer. Cash accounting counts a sale when the retailer pays for the order in full.

By definition, EBIT is available to pay lenders, governments and shareholders. Since interest expense is tax-deductible, operating managers could minimize corporate taxes by increasing corporate leverage: pre-tax earnings are used to pay interest expense on debt, and money that would have been paid in corporate taxes is paid to commercial lenders.

Since the tax-deductibility of interest expense is unlimited, operating managers could borrow until 100% of EBIT was used for interest payments. Rather than maximize net income, the focus on EBIT paradoxically led corporate managers to minimize net income.

The Shift from EBIT to EBITDA

“Although the company’s $365.4 million quarterly loss was also larger than expected, Global Crossing added $2.5625, to $27.875, in trading yesterday. Cash flow at Global Crossing, which is based in Hamilton, Bermuda, was $1.415 billion, compared with the $1.295 billion forecast. Global Crossing’s chief executive, Leo J. Hindery Jr. told analysts that the company now views its previous estimates of cash flow and sales for 2000 as ‘understated as it presses forward with plans to make nearly all of its fiber optic cable systems around the world operational by next year.'”

As a proxy for cash flow, EBITDA was popularized by John Malone, the former CEO of Tele-Communications Inc. Subsequently, many of John Malone’s former deputies have also advanced EBITDA as a proxy for cash flow, albeit with mixed results.

As a proxy for cash flow, the emphasis on EBITDA continued the upward move on the income statement from post-tax earnings (EPS) to pre-tax earnings (EBIT). In the early years, Bob Magness and John Malone sought funding from the high-yield market, primarily from Michael Milken at Drexel Burnham Lambert. In order to create higher valuations, John Malone’s premise was simple: convince Wall Street to move higher up the income statement, and John Malone convinced Wall Street to focus on a higher number.

As an operator of regulatory monopolies, John Malone emphasized EBITDA rather than EBIT, and John Malone’s emphasis on EBITDA consequently deemphasized capital expenditures. However, “depreciation is a non-cash expense” is a misnomer, since capital depreciation is a capital expense.

Despite its analytical flaws, EBITDA became the principal determinant of value and led to systematic overvaluations. Theoretically, EBITDA – CapEx is a proxy for free cash flow in a mature business with minimal capital expenditures. However, the cable industry was a rapidly-growing, capital-intensive business which was was investing heavily in capital expenditures.

Despite its faulty premise, proponents of EBITDA promised increased comparability, since EBITDA “adjusted” for the following elements:

- interest expense: a function of capital structure

- tax expenses: a function of geography and legal structure

- working capital: the investment in short-term investments

- depreciation: the investment in long-term investments

Pretax Cash Flow = Pretax Earnings + Capital Depreciation

As a flawed measure of cash flow, EBITDA obfuscates the multiple sources of pretax cash flow: (i) pretax earnings and (ii) capital deprecation. Pretax earnings are the return on the capital invested in a business, while capital depreciation is a return of the capital invested in a business.

“Depreciation is a non-cash expense” is a misnomer: capital depreciation is a capital expense, not an operating expense. On the balance sheet, accumulated depreciation is a contra asset account against long term-assets. On the cash flow statement, capital depreciation is reclassified from an operating expense to an capital expense.

Capital expenditures are essentially prepaid expenses: capital expenditures are made in advance, and capital depreciation is the delayed recording of this cash expense. Conceptually, capital depreciation is a source of capital, and capital expenditures are a use of capital. Despite the expense’s timing mismatch, capital depreciation is a direct offset to capital expenditures.

An overleveraged company that has spent its capital depreciation allowance on debt service may be unable to replace depreciated long-term assets. Further, overleveraged companies experiencing corporate distress will have limited access to external financing, and overleveraged companies will eventually be forced into bankruptcy or liquidation.

What is cash flow?

Cash flow is measured by the cash flow statement, and the cash flow statement is essentially a reconciliation of the year-over-year changes in the balance sheet. Cash flow has a multitude of definitions, including cash flow from operations, free cash flow, free cash flow to equity and free cash flow to the firm.

- CFO: Cash flow from operations is provided by the cash flow statement, and cash flow from operations is a GAAP-metric. CFO is the levered measure of cash flow from operations. Amortization is added, because amortization is generally a non-cash expense. Capital depreciation is added, because capital depreciation is a capital expense. Cash flow from operations includes investments in short-term assets (i.e. working capital), but cash flow from operations does not include investments in long-term assets (i.e. capital expenditures).

- FCF: Free Cash Flow is generic term and is provided by the cash flow statement. FCF is obtained by deducting capital expenditures from cash flow from operations. Free cash flow is “free,” because it represents the amount of cash flow that is available for discretionary spending, i.e. distribution to the company’s securities holders.

- FCFE: Free Cash Flow to Equity is a measure of levered free cash flow, and FCFE represents the cash flow available to equity investors. Free Cash Flow to Equity begins with cash flow from operations, deducts capital expenditures and adds net debt issued. FCFE is the variable used to determine the equity value of a firm.

- FCFF: Free Cash Flow to the Firm is a measure of unlevered free cash flow, and FCFF represents the cash flow available to the company’s securities holders. Generally, this is a hypothetical calculation: EBIT*(1-t) represents the unlevered net earnings, amortization and depreciation are added, investments in short-term assets (i.e. working capital) are subtracted, and investments in long-term assets (i.e. capital expenditures) are subtracted. FCFF is the variable used to determine the total value of a firm.

Cash flow is more objective than accounting earnings; cash flow is harder to manipulate than accounting earnings, although cash flow can be increased by (i) increasing corporate leverage and (ii) reducing capital expenditures.

Operating managers increase corporate leverage in order to increase cash flow, since a highly-leveraged firm has greater cash flow than a similar firm using less leverage. And, operating managers project steadily increasing cash flow based on sharply reduced capital expenditures.

Often, operating managers increase corporate leverage *and* reduce capital expenditures. Unfortunately, these short-term palliatives lead to the long-term erosion of corporate value. An over-leveraged company with depleted long-term assets will probably be forced into a restructuring or a reorganization.

If capital depreciation exceeds capital expenditures, investors should expect a decline in operating results. Operating managers cannot spend depreciation allowance on debt-service and expect to remain competitive.

A company spends money on long-term assets in order to generate cash flow: a company must reinvest its depreciation allowance. A company is gradually being liquidated if the sustained level of capital expenditures is lower than the sustained level of capital depreciation.

Operating managers are generally best positioned to understand the capital expenditures necessary to create, to sustain and to expand a company’s competitive advantage. At a minimum, capital expenditures will need to exceed capital depreciation by the cost of inflation, since capital depreciation numbers are based on historical cost.

Is Adjusted EBITDA a suitable proxy for cash flow?

“Both before and after this conference call, I spoke with some of the financial analysts in the company. I began to learn that there was a general sense of uneasiness about these swap transactions and in particular about a transaction with 360 Networks. Through discussions with various people, I learned that 360 Networks and Global Crossing had entered into a last-minute transaction wherein Global booked $150 million in Cash Revenues even though it had not received a penny in cash . . . I also told him there were a number of people in the office concerned about the accounting for those swap transactions, particularly the inclusion of $150 million cash relating to the 360 Networks transaction in cash revenue and adjusted EBITDA when no cash was received.”

Despite EBITDA’s analytical flaws, operating managers creatively seek to address the limitations of EBITDA with the use of ‘adjusted EBITDA.’ As Global Crossing demonstrated, Adjusted EBITDA is a cure that is worse than the disease.

Accounting earnings complement cash flows, but EBITDA (and its derivations) are generally misleading proxies for cash flow. If capital expenditures are greater than or equal to capital depreciation, EBITDA will generally overstate CFO, FCF, FCFE, and FCFF.

Conclusion: Investors prefer free cash flow

FCFE = CFO – CapEx + Net Debt Issuance

FCFF = FCFE + Net Borrowing – Int*(1-t)

Cash flow is a generic term with a multitude of definitions, including cash flow from operations, free cash flow, free cash flow to equity and free cash flow to the firm. The choice of the cash flow definition depends on the facts and circumstances of the specific situation as well as the investor’s position in the capital structure.

Investors generally prefer free cash flow, a non-GAAP metric that represents the cash flow that is available to a company’s securities holders. Free cash flow also captures the notion that capital expenditures are necessary to create, to sustain and to expand a company’s competitive advantage.